Home

The Knights Templar were established c.1119 and given papal recognition in 1129. It was a Catholic medieval military order whose members combined martial prowess with a monastic life to defend Christian holy sites and pilgrims in the Middle East and elsewhere. The Templars, with headquarters at Jerusalem and then Acre, were an important and elite element of Crusader armies.

Eventually, the Knights Templar became a very powerful body and they came to control both castles and lands in the Levant and across Europe. Accused of heresy, corruption, and performing forbidden practices, the order was attacked by the French king Philip IV (r. 1285-1314) on Friday 13 October 1307 and then officially disbanded by Pope Clement V (r. 1305-1314) in 1312.

Foundation & Early History

The order was formed c. 1119 when seven knights, led by a French knight and nobleman from Champagne, Hugh of Payns, swore to defend Christian pilgrims in Jerusalem and the Holy Land and so created a brotherhood who took monastic vows, which included vows of poverty, and lived together in a closed community with an established code of conduct. In 1120 Baldwin II, the king of the Kingdom of Jerusalem (r. 1118-1131), gave the knights his palace, the former Aqsa Mosque on the Temple Mount of Jerusalem, for use as their headquarters. The building was commonly referred to as ‘The Temple of Solomon‘ and so the brotherhood quickly became known as ‘the Order of the Knights of the Temple of Solomon’ or simply the ‘Templars’.

Officially recognised as an order by Pope Honorius II (r. 1124-1130) at the Council of Troyes in January 1129 (the first such military order to be created), the Templars were initially considered a branch of the Cistercians. In 1145, knights of the order were granted permission to wear the white hooded-mantle Cistercian monks had made their own. The knights soon adopted their distinctive white cloak and they began to use the insignia of a red cross on a white background. There was no impediment to fighting as regards to religious doctrine, provided that the cause was a just one – the Crusades and defence of the Holy Land being just such a cause – and so the order received the official support of the Church. The first major battle involving Templar knights was in 1147 against the Muslims during the Second Crusade (1147-1149).

DONATIONS TO THE ORDER CAME IN ALL FORMS, BUT MONEY, LAND, HORSES, MILITARY EQUIPMENT, & FOODSTUFFS WERE THE MOST COMMON.

The order grew thanks to donations from supporters who recognised their important role in the protection of the small Christian states in the Levant. Others, from the humblest to the rich, gave what they could to simply help ensure both a better afterlife and, because donors could be mentioned in prayer services, perhaps a better life in the here and now. Donations came in all forms, but money, land, horses, military equipment, and foodstuffs were the most common. Sometimes privileges were donated which helped the order save on its own expenses. The Templars invested their money, too, buying revenue-producing properties so that the order came to own farms, vineyards, mills, churches, townships or anything else they thought a good investment.

Another boost to the order’s coffers was booty and new land acquired as the result of successful campaigns while tribute could also be extracted from conquered cities, lands controlled by Templar castles, and weaker rival states in the Levant. Eventually, the order was able to establish subsidiary centres in most of the states of western Europe, which became important sources of revenue and new recruits.

Money may have poured in from all corners of Europe but there were high costs to be met, too. Maintaining knights, their squires, horses (knights often had four each), and armour and equipment were all drains on the Templars’ finances. There were taxes to be paid to the state, donations to the Papacy, and sometimes tithes to the church, as well as payoffs to be made to local dignitaries, while performing masses and other services had their not insignificant costs, too. The Templars also had a charitable purpose and were supposed to help the poor. One-tenth of bread produced, for example, was distributed to the needy as alms. Finally, military disasters resulted in losses of both men and property in enormous quantities. The exact accounts of the Templars are not known, but it is more than likely that the order was never quite as rich as everyone thought they were.

From the mid-12th century, the Templars widened their influence and fought in the crusade campaigns in Iberia (the ‘Reconquest’) for various rulers in Spain and Portugal. Also operating in the Baltic crusades against pagans, by the 13th century the Knights Templar owned estates from England to Bohemia and had become a truly international military order with tremendous resources at its disposal (men, arms, equipment, and a sizeable naval fleet). The Templars had established a model which would be copied by other military orders such as the Knights Hospitaller and Teutonic Knights. There was one area, though, in which the Templars truly excelled: banking.

Medieval Bankers

Regarded as a safe place by locals, Templar communities or convents became repositories for cash, jewels, and important documents. The order had their own cash reserves which were, from as early as 1130, put to good use in the form of interest-gaining loans. The Templars even permitted people to deposit money in one convent and, provided they could show a suitable letter, transfer and then withdraw equivalent money from a different convent. In another early banking service, people could hold what today would be called a current account with the Templars, paying in regular deposits and arranging for the Templars to pay out, on behalf of the account holder, fixed sums to whoever was nominated. By the 13th century, the Templars had become such proficient and trusted bankers that the kings of France and other nobles kept their treasuries with the order. Kings and nobles who embarked on crusades to the Holy Land, in order to pay their armies on the spot and meet supply needs, often forwarded large cash sums to the Templars which could be withdrawn later in the Levant. The Templars even lent money to rulers and thus became an important element in the increasingly sophisticated financial structure of late medieval Europe.

Organisation & Recruitment

Recruits came from all over western Europe, although France was the largest single source. They were motivated by a sense of religious duty to defend Christians everywhere but especially the Holy Land and its sacred sites, as a penance for sins committed, as a means to guarantee entry into heaven, or more earthly reasons such as a search for adventure, personal gain, social promotion or simply a regular income and decent meals. Recruits had to be free men of legitimate birth, and if they wished to become medieval knights they had, from the 13th century, to be of knightly descent. Although rare, a married man could join provided his spouse agreed. Many recruits were expected to make a significant donation on entering the order, and as debts were a no-no, the financial status of a recruit was certainly a consideration. Although some minors did join the order (sent by their parents, of course, in the hope of a useful military training for a younger son who would not inherit the family estate), most new recruits to the Templars were in their mid-20s. Sometimes recruits came late in life. An example is the great English knight Sir William Marshal (d. 1219), who, like many nobles, joined the order just before his death, left them money in his will, and so was buried in Temple Church, London where his effigy may still be seen today

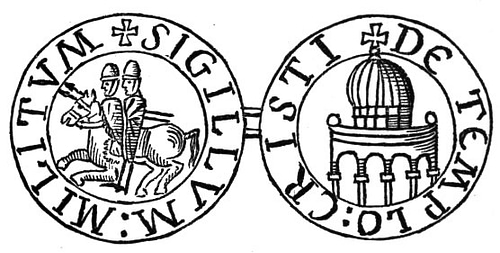

There were two ranks within the order: knights and sergeants, with the latter group including non-military personnel and laymen. Most recruits were for the second group. Indeed, the number of knights across the order was surprisingly few. There were perhaps only a few hundred full-brother Templar knights at any one time, sometimes rising to 500 knights in times of intense warfare. These knights would have been greatly outnumbered by other soldiers used by the order such as infantry (the sergeants or recruits from vassal lands) and mercenaries (especially archers), as well as squires, baggage bearers, and other non-combatants. Other members of the order included priests, craftsmen, labourers, servants, and even some women who were members of affiliated nunneries.THE ORDER WAS LED BY THE GRAND MASTER WHO STOOD AT THE TOP OF A PYRAMID OF POWER. CONVENTS WERE GROUPED INTO GEOGRAPHICAL REGIONS KNOWN AS PRIORIES.The order was led by the Grand Master who stood at the top of a pyramid of power. Convents were grouped into geographical regions known as priories. In troubled zones like the Levant, many convents were in castles while elsewhere they were established to control areas of land the order owned. Each convent was managed by a ‘preceptor’ or ‘commander’ and reported to the head of the priory in which his convent was situated. Letters, documents and news reports went back and forth between convents, all carrying the seal of the order – most commonly two knights on a single horse – in order to foster some unity between distant branches. Convents typically sent one-third of their revenue to the order’s headquarters. The Grand Master resided in the headquarters at Jerusalem, and then Acre from 1191, and Cyprus after 1291. There he was assisted by other high-ranking officials such as the Grand Commander and Marshal along with lesser officials in charge of specific supplies such as clothing. There were occasional meetings or chapters of representatives from across the order and chapters at provincial level, too, but there seems to have been a great deal of autonomy in local convents, and only episodes of gross misconduct were ever sanctioned.Uniform & RulesKnights took vows on entering the order, much like in monasteries, although not so strict and without the restriction of always remaining inside their communal accommodation. Obedience to the Grand Master was the most important promise to be made, attendance at church services was compulsory, celibacy too, and communal meals a given (which did, every odd day, include meat). Worldly pleasures were not permitted, and these included such quintessentially knightly pastimes as hunting and hawking and not wearing flashy clothing and arms which normal knights were famous for. For example, belts were often a medium for decoration, but the Templars wore only a simple wool cord belt to symbolise chastity.Templar knights wore a white surcoat and cloak over their armour, as already mentioned, and carried a red cross on their left breast. The red cross also appeared on the livery of horses and on the order’s pennant. This made them distinct from the Knights Hospitaller (who wore a white cross on a black background) and the Teutonic Knights (who wore a black cross on a white background). Templar shields, in contrast, were usually white with a thick black horizontal stripe across the top. Sergeants wore a brown or black mantle or cloak. Another distinguishing feature of Templars was that they all grew beards and had short (by medieval standards) hair.Brother knights could have their own personal property (movable or fixed), unlike in some other military orders. Things were a little less strict in terms of clothing, too; the Templars being allowed to wear linen in spring and summer (not just wool), a decision no doubt appreciated by members in warmer climes. If any of the regulations of the order, known collectively as the Rule, were not followed, then members were punished which might range from a withdrawal of privileges to flogging and even life imprisonment.The Crusades Skilled with the lance, sword and crossbow, and well-armoured, the Knights Templar and other military orders were the best trained and equipped of any members of a Crusader army. For this reason, they were often deployed to protect the flanks, vanguard and rear of an army in the field. The Templars were particularly renowned for their disciplined group cavalry charges when, in tight formation, they blasted through enemy lines and caused havoc which could then be exploited by allied troops following up their advance. They were also highly disciplined both in battle and in camp, with severe penalties imposed on knights not following orders, including expulsion from the order for losing one’s sword or horse through carelessness. That being said, the order as a whole could prove difficult for a Crusade commander to keep check on, given that they were often the most zealous and eager troops to win honour and glory.

Uniform & Rules

Knights took vows on entering the order, much like in monasteries, although not so strict and without the restriction of always remaining inside their communal accommodation. Obedience to the Grand Master was the most important promise to be made, attendance at church services was compulsory, celibacy too, and communal meals a given (which did, every odd day, include meat). Worldly pleasures were not permitted, and these included such quintessentially knightly pastimes as hunting and hawking and not wearing flashy clothing and arms which normal knights were famous for. For example, belts were often a medium for decoration, but the Templars wore only a simple wool cord belt to symbolise chastity.

Templar knights wore a white surcoat and cloak over their armour, as already mentioned, and carried a red cross on their left breast. The red cross also appeared on the livery of horses and on the order’s pennant. This made them distinct from the Knights Hospitaller (who wore a white cross on a black background) and the Teutonic Knights (who wore a black cross on a white background). Templar shields, in contrast, were usually white with a thick black horizontal stripe across the top. Sergeants wore a brown or black mantle or cloak. Another distinguishing feature of Templars was that they all grew beards and had short (by medieval standards) hair.

Brother knights could have their own personal property (movable or fixed), unlike in some other military orders. Things were a little less strict in terms of clothing, too; the Templars being allowed to wear linen in spring and summer (not just wool), a decision no doubt appreciated by members in warmer climes. If any of the regulations of the order, known collectively as the Rule, were not followed, then members were punished which might range from a withdrawal of privileges to flogging and even life imprisonment.

The Crusades

2Skilled with the lance, sword and crossbow, and well-armoured, the Knights Templar and other military orders were the best trained and equipped of any members of a Crusader army. For this reason, they were often deployed to protect the flanks, vanguard and rear of an army in the field. The Templars were particularly renowned for their disciplined group cavalry charges when, in tight formation, they blasted through enemy lines and caused havoc which could then be exploited by allied troops following up their advance. They were also highly disciplined both in battle and in camp, with severe penalties imposed on knights not following orders, including expulsion from the order for losing one’s sword or horse through carelessness. That being said, the order as a whole could prove difficult for a Crusade commander to keep check on, given that they were often the most zealous and eager troops to win honour and glory.

Knight Templar Broadcasting Limited Monkstown Farm Dun Laoghaire Co Dublin Ireland Phone +353864411394